Lyme Disease

What is Lyme Disease?

Julia Behrens has chosen to specialize in supporting people with Lyme’s and co-infections, which arose from her multi-systemic approach to medicine. Specifically, over the last 10 years she has attended numerous conferences across Europe concerned with Lyme’s, working in a Lyme clinic and conducting personal research and collaborated with healthcare professionals across the board.

Julia speaks fluent German and is on contact with German clinics and labs She has a depth of understating of other leading Practitioner in the Lyme field such as s such as Stephan Buhners, Dr Horowitz, Dr. Klinghardt, working with Byron white formulas and Cowden protocol.

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection spread to humans by infected ticks. Ticks are tiny arachnids found in woodland areas that feed on the blood of mammals, including humans. Tick bites often go unnoticed and the tick can remain feeding for several days before dropping off. The longer the tick is in place, the higher the risk of it passing on the infection.

Borrelia is a spirochete which infects Ticks and it has many species it behaves like a bacterian and parasite. Causing symptoms of Lyme disease. Lyme disease can affect your skin, joints, heart and nervous system.

Treatment of Lyme Disease

NHS treatment of Lyme Disease is limited. There is a suggested treatment pathway in place but this only applies to those diagnosed shortly after infection and only includes treatment through antibiotics which is often not provided for long enough.

Herbal medicine has been helpful for some in reliving longer term symptoms with patients that have been suffering for years. A holistic health care system looks at the the inter connection and workings of the whole body.

Supporting individual may look at traditional medicines, such as antibiotics, but also looking at complementary and alternative medicines which have been shown to be of benefit.

What are the symptoms of Lyme disease?

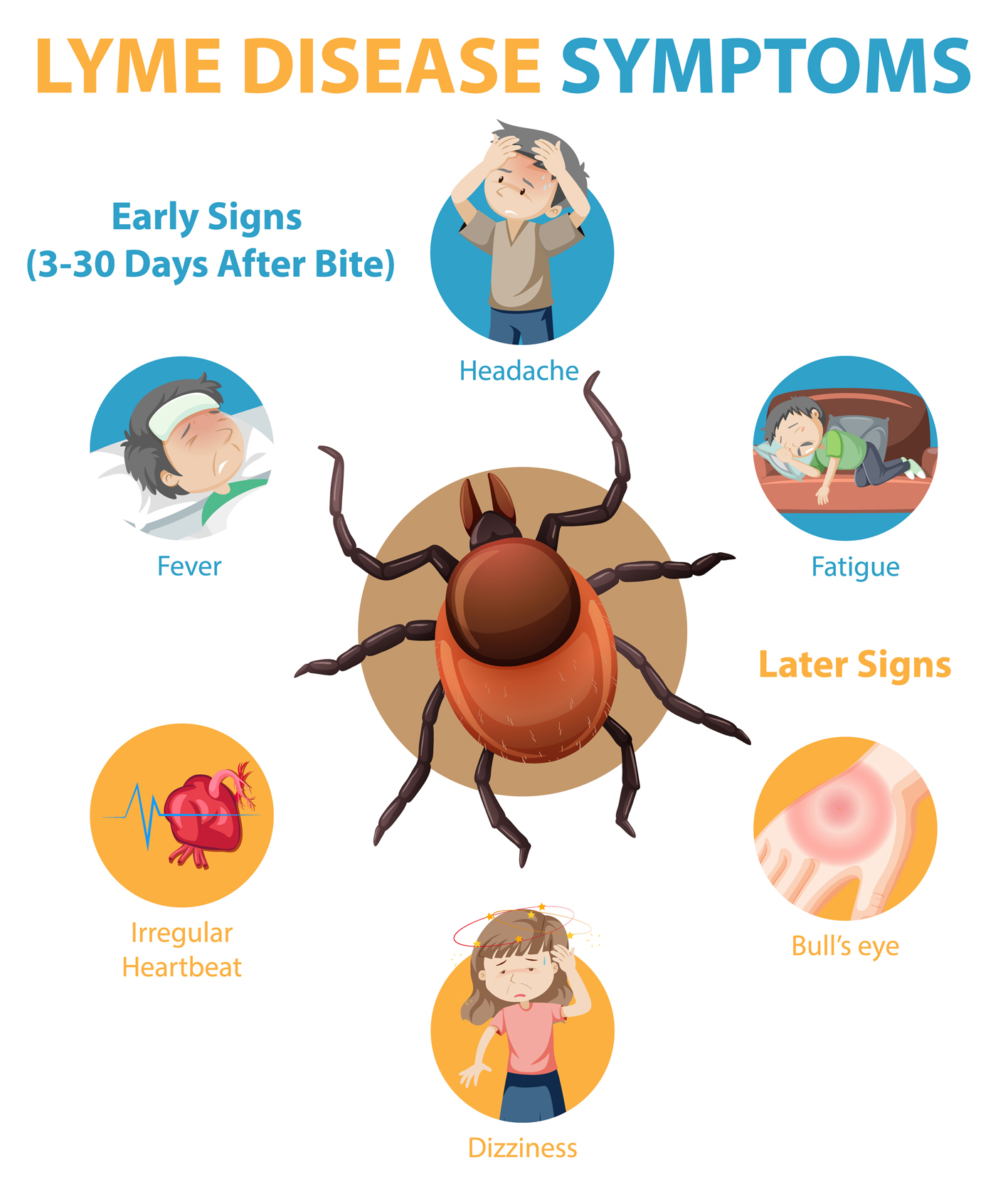

The symptoms and effects of Lyme disease can be divided into three stages:

Stage one – early reaction to the local skin infection

This can develop at any time between 3 and 36 days after being bitten by an infected tick.

Rash – the classical symptom of Lyme disease is a typical rash called erythema migrans. However, this does not always occur. It may depend on which species of borrelia is involved. In the UK, most people with Lyme disease have or have had this rash.

The rash is usually a single circular red mark that spreads outwards slowly over several days. The circle gets bigger and bigger with the centre of the circle being where the tick bite occurred. As it spreads outwards, a paler area of skin emerges on the inner part of the circle. Therefore, the rash is often called a ‘bullseye’ rash.

The rash usually spreads over at least 5 cm, but may be much bigger.

The rash is not usually painful or particularly itchy. You may not even notice it if it is on your back. Without treatment, erythema migrans typically fades within 3-4 weeks. However, just because the rash fades does not necessarily mean the infection has cleared from the body.

Note: many insect bites cause a small red blotchy ‘allergic’ rash to appear soon after the skin is bitten. These soon go away. The rash of erythema migrans is different in that it usually develops several days after the bite, lasts for longer, and has a typical spreading circular appearance.

Flu-like symptoms – these occur in about a third of cases. Symptoms include tiredness, general aches and pains, headache, fever, chills and neck stiffness. These symptoms are often mild and go within a few days, even without treatment (but the infection may not have gone).

In some cases, the infection does not progress any further, even without treatment, as the immune system may clear the infection. However, in some cases that are not treated, the disease progresses to stage two.

Stage two – early disseminated disease

This may develop in untreated people weeks or months after the bite. Disseminated means spread around the body away from the site of the original infection. Symptoms are variable but can include one or more of the following:

Joint problems – in one or more joints. They most commonly affect the knee joint. The severity of joint problems can range from episodes of mild joint pains, to severe joint inflammation (arthritis) causing a lot of pain. Episodes of joint inflammation last, on average, three months.

Nerve and brain problems – some affected people develop inflammation to nerves, particularly the nerves around the face. This may cause the nerve to stop working and result in facial weakness. Inflammation of the tissues around the brain (menigitis) and inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) may occur.

Heart problems – some affected people develop inflammation of the heart (myocarditis) and other heart problems. This may cause symptoms such as dizziness, breathlessness, chest pain and a feeling that your heart is beating in a fast, irregular way (palpitations).

Rash – several areas of the skin (not where the tick bite occurred) may develop a rash similar to erythema migrans (described above). These ‘secondary’ rashes tend to be smaller than the original stage one rash. These tend to fade within 3-4 weeks. Occasionally, blue-red nodules called lymphocytomas may develop on the skin, particularly on ear lobes and nipples.

Rarely, other organs such as the eyes, kidneys and liver are affected.

Stage three – persistent (chronic) Lyme disease

This may develop months to years after infection. It may develop after a period of not having any symptoms. A whole range of symptoms have been described in joints, skin, nerves, brain and heart. The brain problems may include mild confusion, and problems with memory, concentration, mood, personality and balance. It occasionally may cause a schizophrenic-like illness. There may be tiredness and joint pains which have been called “post-Lyme syndrome” with symptoms similar to fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome.

Diagnosing Lyme Disease

Lyme disease can be a difficult condition to diagnose, particularly in its latter stages. This is because its symptoms are also shared by more common conditions such as infections and arthritis.

A characteristic pink or red “bull’s-eye” rash of Lyme disease may develop, usually within 30 days of being bitten. However, in up to a third of cases of Lyme disease, there is no rash.

GPs are generally able to diagnose and treat acute Lyme disease i.e. those patients that notice they have been bitten and present within 24-48 hours of their rash appearing. Antibiotics will be given for approximately 2-4 weeks and this usually clears up the infection and stops other symptoms developing.

The diagnosis of persistent chronic Lyme disease is more difficult and a particularly new area for the NHS. This means many GPs are not aware of the disease nor how to treat it. Some may offer testing (see below) and if diagnosed the standard 2-4 weeks of antibiotics will be given but research has shown that this is often not long enough. Lyme Disease Action (LDA) state that:

‘The bacteria that cause Lyme disease have a very long life cycle, reside in human tissues with a poor blood supply (e.g. tendons) and have the ability to evade the immune system. These factors, among others, make it hard to eradicate. There is ample evidence in the scientific literature of viable bacteria isolated from treated patients and it is likely that in some cases continuing symptoms are due to still active infection’.

Testing

Tests on the NHS for Lyme disease need to be carried out at least a few weeks after you were bitten by the tick because it can take this long for the infection to develop. You may need to be re-tested if Lyme disease is still suspected after a negative test result.

The tests used to help diagnose Lyme disease are:

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test

- Western Blot test

ELISA test

The first test you will have is a type of blood test known as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test. The ELISA test looks for specific antibodies produced by your immune system to kill the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria.

The ELISA test is not 100% accurate as it can sometimes produce a positive result even when a person is not infected with Lyme disease (known as a false-positive result). This may happen if a different condition is causing your symptoms, such as syphilis, glandular fever or rheumatoid arthritis.

Because of this, a positive ELISA test is followed by a further test known as the Western Blot test.

Western Blot test

The Western Blot test involves taking a small blood sample. The proteins in the blood are separated and placed on a thin sheet of permeable material. The proteins can then be studied for antibodies used by the immune system to fight the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi which causes Lyme disease.

If both the results of the ELISA test and the Western Blot test are positive, a confident diagnosis of Lyme disease can usually be made.

When sending ticks to UKHSA, it’s essential to ensure their safe and secure transit. We accept both live and dead ticks for identification, but if you’re sending live ticks, please use the first-class mail service.

To send ticks, follow these steps carefully:

- Packaging: Package the ticks in a small plastic container that is securely fastened. Alternatively, you can request a screw-top plastic vial by emailing tick@ukhsa.gov.uk.

- Protection: Place the container inside a padded envelope to provide extra protection during transportation.

- Return Address: Ensure that your package has a visible return address, so we can reach out if needed.

- Marking: For live ticks, mark the package as ‘urgent – live creatures.’ This marking is not necessary for dead ticks.

- Recording Form: Include a completed recording form along with your package.

Send to:

Tick Surveillance Scheme, UK Health Security Agency Porton Down Salisbury Wiltshire SP4 0JG

Your cooperation in following these guidelines ensures the safe and effective handling of ticks for identification. If you have any further questions or require assistance, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

How common is Lyme disease?

Since 1975 when it was first noted, thousands of cases have been reported in the USA. Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne infectious disease in the UK, Europe and North America. People who spend time in woodland or heath areas are more at risk of developing Lyme disease because these areas are where tick-carrying animals, such as deer and mice, live.

Public Health England estimates there are 2,000 to 3,000 cases of Lyme disease in England and Wales each year, and that about 15% of cases occur while people are abroad.

Cases of Lyme disease have been reported throughout the UK, but areas known to have a particularly high population of ticks include:

- Exmoor

- the New Forest in Hampshire

- the South Downs

- parts of Wiltshire and Berkshire

- Thetford Forest in Norfolk

- the Lake District

- the Yorkshire Moors

- the Scottish Highlands

Most tick bites happen in late spring, early summer and autumn because these are the times of year when most people take part in outdoor activities, such as hiking and camping.

Causes of Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria. The bacteria are present in the blood of many different animals including mice, deer, pheasants and blackbirds.

If a tick (a tiny arachnid) bites an animal that has the bacteria, the tick can also become infected. The tick can then transfer the bacteria to a human by biting them and feeding on their blood.

Ticks are very small and their bites are not painful, so you may not realise you have one attached to your skin. However, there is a higher risk you will become infected if the tick remains attached to your skin for more than 24 hours.

Once infected, the bacteria moves slowly through your skin into your blood and lymphatic system. The lymphatic system helps fight infection and is made up of a series of vessels (channels) and glands (lymph nodes).

Left untreated, the bacteria that causes Lyme disease can damage the joints and the nervous system, leading to later symptoms of Lyme disease.

Where are ticks found?

Ticks can be found in any areas with deep or overgrown vegetation where they have access to animals to feed on.

Although this means they are most common in woodland and heath areas, they may also be found in gardens or parks where this kind of vegetation exists.

Cases of Lyme disease have been reported throughout the UK, but the infection is most commonly acquired in the southern counties of England. Around 15% of infections occur abroad.

Groups at risk

The groups most at risk of getting Lyme disease include those who work in woodland and heath areas and those who take part in activities in these areas. For example:

- hikers

- campers

- farmers

- forestry workers

- soldiers

- gamekeepers

Most tick bites occur in late spring, early summer and autumn because these are the times of year when most people take part in outdoor activities, such as hiking and camping.

Preventing Lyme disease

There is currently no vaccine to prevent Lyme disease. In 2002, a vaccine was introduced in America but was later withdrawn because of concerns over side effects. The best way of preventing Lyme disease is to avoid being bitten when you are in wooded or heath areas known to have a high tick population. The following precautions might help prevent Lyme disease:

- Wear a long-sleeved shirt.

- Tuck your trousers into your socks.

- Use insect repellent. camphor, T tree, eucalyptus etc)

- Check yourself for ticks. Remove ticks a.s.a.p with TICK REMOVERS.

- Check your children and pets for ticks. Do not pick ticks of pets by hand. Many people have become infected this way.

- Astragalus: if you live in a Lyme endemic area, and/or work in the outdoors, take Astragalus membranaceous all year round.

- If bitten, take Andrographis capsules x 3 x qds for three weeks/and or course of Doxycycline

If you do find a tick on your or your child’s skin, remove it by gently gripping it as close to the skin as possible, preferably using fine-toothed tweezers, and pull steadily away from the skin.

Never use a lit cigarette end, a match head or essential oils to force the tick out.

Removal of an attached tick within the first 24 hours will usually result in the person remaining uninfected (the spirochete takes its time once the tick has latched on, to rearrange its outer protein coat to best match the host animal)

Recommended Reading

Julia highly recommend getting Stephen Harrod Buhner book on Lyme disease. He is an authoritative herbalist in the united states on Lyme disease his book on this subject is called Healing Lyme: Natural Healing of Lyme Borreliosis and the Coinfections Chlamydia and Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis, 2nd Edition published in 2015. This edition covers Lyme disease, the symptoms of Lyme disease, natural treatment of Lyme disease and all its coinfections and complications.

Lyme Form Downloads

Please complete this form before your initial Lyme appointment. Download the interactive form, complete the fields, save the file and email to julia@herbal-consultant.com

Please complete this form before your follow up Lyme appointment. Download the interactive form, complete the fields, save the file and email to julia@herbal-consultant.com